Most investors in emerging markets might think they are getting broad exposure to the developing world. However, this is far from the truth as the EM benchmark allocates over 80% to only six countries, some of which are arguably no longer “emerging”. Not only is this a problem for ETF investors – most active EM funds’ country allocations are also tethered to this benchmark.

We believe the other fifty emerging markets present a tremendous untapped opportunity for truly active investors in terms of both diversification and performance. We outline our rationale below.

1. Mainstream EM severely lacks diversification

The term ‘emerging markets’ was coined in the early 1980s by Antoine van Agtmael, an economist at the IFC who was looking for a marketing catchphrase for ‘third world countries’. The new aspirational term was supposed to be less offensive and denote countries on a journey toward a better future. (Fortunately, Donald Trump’s 2018 re-coining of the term didn’t stick).

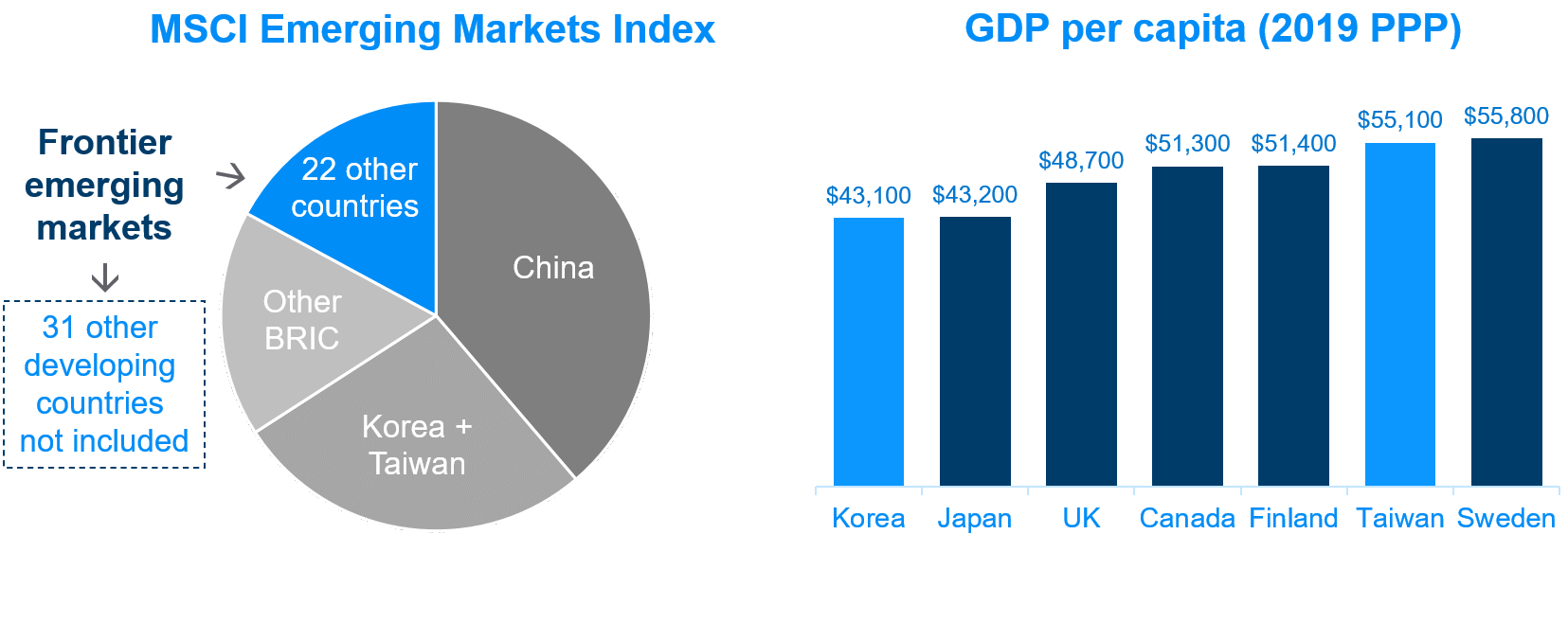

Today, ‘emerging markets’ refers more commonly to a financial benchmark classification than development economics. The most popular benchmark is MSCI Emerging Markets, which puts six countries at more than 80% of its weight (China at 40% with five others totaling another 40% – the other so-called BRIC countries plus Korea and Taiwan), leaving less than 20% for 22 other emerging markets while an additional 31 developing countries are excluded altogether. This is more of a recent phenomenon: China only hit 10% of the index in 2006, then 20% in 2014, 30% in 2018, and 40% in 2020 largely as a result of MSCI’s decision to include Chinese domestically listed shares in the index (previously only Chinese shares listed abroad were included). Meanwhile, Mexico, South Africa, Thailand and Malaysia, which once held double-digit positions, now all contribute less than a few percent each. This is why we affectionately refer to the MSCI Emerging Markets Index as the “China index.”

Some of the top-6 countries in the index are arguably no longer emerging markets at all. For example, Korea’s and Taiwan’s highly innovative economies’ GDP per capita is similar to GDP of Finland and Sweden. Furthermore, China is already the world’s second-largest economy with a literacy rate of 97%, more college students than any other country, more high-speed rail mileage than all other countries combined, and is home to the world’s second-largest and third-largest stock and bond markets. Taken together, these three advanced economies represent two-thirds of the EM index, clearly failing to provide investors with diversified exposure to the developing world.

On the other hand, the fifty neglected emerging markets offer an abundant range of options. There are well over 1,000 listed companies with sufficient trading liquidity in the markets outside the top-6, many of which are fundamentally compelling companies – high-quality growing businesses trading at low valuations. Many fund managers overlook this opportunity set in favor of hugging the index.

Source: MSCI, World Bank.

2. Fewer investors means less efficient markets

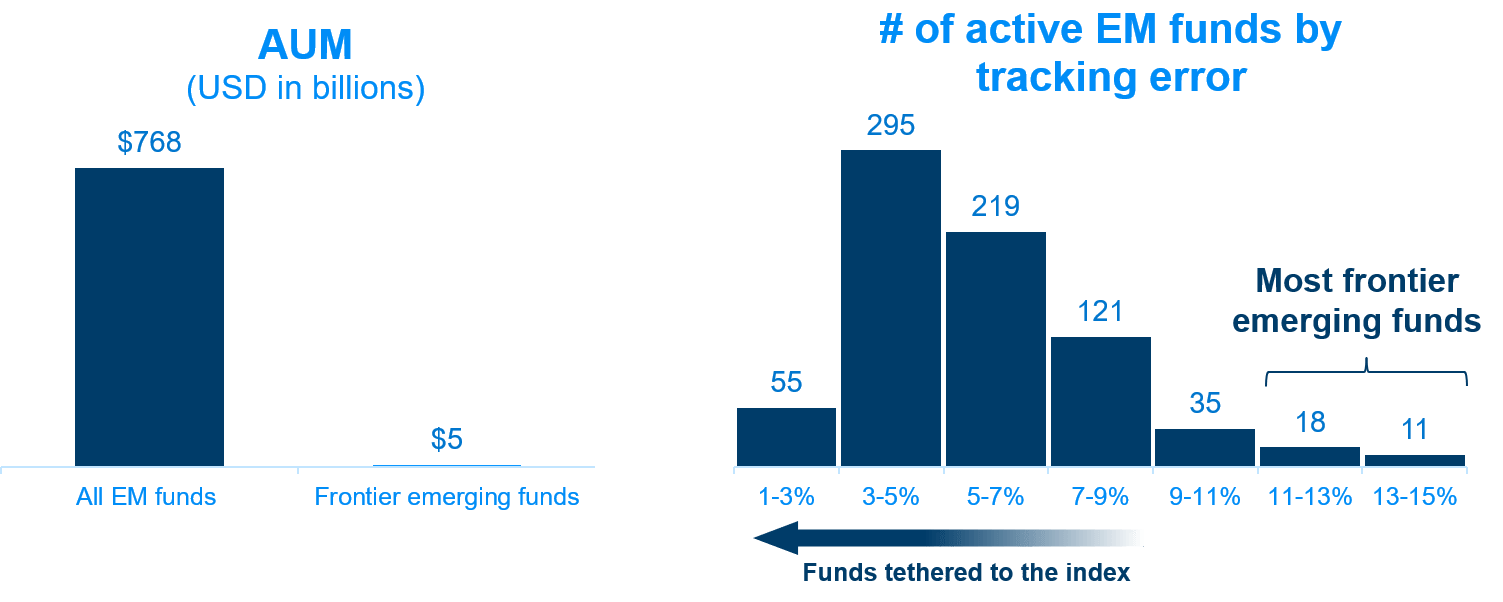

The competence of fund managers is usually assessed by their ability, or failure, to generate returns that exceed those of the dominant index in their asset class. So in order to reduce the risk that a fund manager egregiously underperforms and thus suffers track-record impairment, faces client redemptions, or gets fired, there is an industry-wide tendency by fund managers to closely mimic the index’s allocations. Any deviations are almost always in the form of ‘underweight’ or ‘overweight’ the index’s allocation, and tend to be narrow. As a result, the vast majority of all active EM funds have shockingly low tracking errors, a measure which indicates how closely funds’ returns mimic the index.

Truly active EM fund managers, on the other hand, allocate capital to the companies with the best investment cases regardless of what the index would dictate. Having this freedom is important: the 50 frontier emerging markets are less efficient, given that they attract far fewer foreign institutional investors than mainstream EM does (out of 1,000 listed EM funds with combined AUM of over $700bn, only 37 funds totaling $5bn AUM invest more than 50% of their portfolio outside the top-6 EM countries). Thus, astute active investors can generate more alpha by finding undiscovered companies in frontier emerging markets and helping them unlock shareholder value through friendly activist engagement.

Exploring our markets’ inefficiencies, in 2020 alone, we were able to find over two dozen compelling investment cases (eight of which doubled from our initial purchase) and proactively engage with their management. For example, because of its name, Malaysian dairy company Johore Tin was mistakenly classified in financial databases as a tin mining company, precluding many investors from even looking at it. We helped the company hire an investor relations professional, create an investor presentation, issue a first-ever quarterly press release, and arrange several analyst calls to reduce market misunderstanding; a name change is currently in the works. Another example was a medical glove manufacturer whose stock price remained flat for over a month after COVID-19 was officially declared a global pandemic partially due to a dearth of quality sell-side coverage (we found only one small mention of the coronavirus in a single brokerage report on the company during this time) before it skyrocketed 1,400%.

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Tracking error calculated using five years of monthly returns relative to MSCI Emerging Markets.

3. Chinese trees don’t grow to the sky

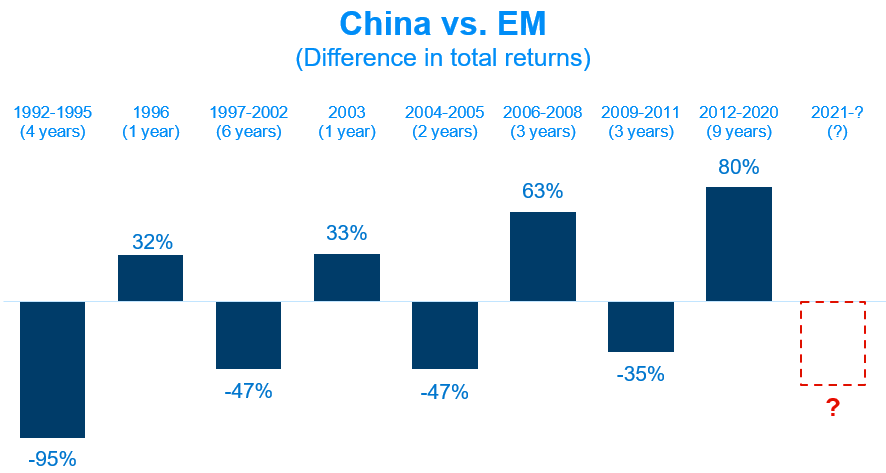

When investors assess the risk that a 40% China weight poses, they might look at the fact that China has delivered a 160% total return over the past nine years while the emerging market index only returned half of that. Indeed, nearly half of the 80% EM return itself actually came from China, with the remainder attributable entirely to Taiwan, Korea, and India, while the other 24 countries in the index merely offset each other.

However, as Howard Marks said, “it is essential to remember that just about everything is cyclical. Cycles always prevail eventually. Nothing goes in one direction forever, trees don’t grow to the sky, few things go to zero, and there’s little that’s as hazardous for investor health as insistence on extrapolating today’s events into the future.”

If one looks at the China-relative-to-EM cycle over time, we appear to be nine years into the longest-running China bull market of the past three decades. This could be in large part due to the massive inflows from ETFs and benchmark-hugging active managers resulting from the EM index’s doubling of China’s weight during this time. It is important to also consider that nearly half of the 160% return from China over the past nine years has come from only two tech stocks: Tencent and Alibaba. Additionally, 2020 was particularly good for equities in China, Korea, and Taiwan as these three countries managed the COVID-19 crisis better than most other emerging markets. But these don’t seem to be replicable events which investors can count on going forward.

To be sure, China has a lot going for it, such as consumption growth driven by the expanding middle class, massive investments in infrastructure, a potentially more predictable relationship with the U.S., and an all-time high appetite for Chinese financial markets by foreign institutional investors. However, it’s not all rosy. Growth rates are slowing, debt levels are concerning, corporate governance is subpar, and economic data cannot always be trusted. Additionally, the complex geopolitical environment adds a degree of external turbulence.

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Indexes used are MSCI China and MSCI Emerging Markets.

4. Frontier emerging markets are not going to zero

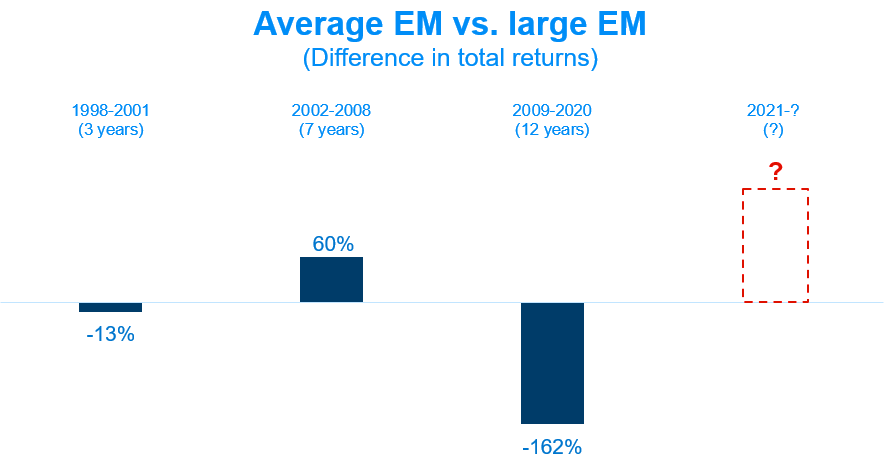

Frontier emerging markets also seem to work in cycles. One way to assess the performance of these markets is to look at an index which equally weights the returns of all emerging markets in order to capture the broad movement in EM stocks and compare it with the mainstream EM index.

Although the average EM country only delivered a measly 53% total return over the past 12 years compared to the mainstream EM index’s 215% (162% underperformance), it should be remembered that smaller EM countries dominated during the last EM bull market from 2002-2008 when they delivered 175% vs. 115% (60% outperformance).

As we wrote in The case for emerging markets: It’s about time, we think we could well be at the very beginning of the next EM bull market. If this proves to be true, instead of concluding that smaller EM countries will indefinitely underperform the heavyweights, we believe now could be the time for the forgotten fifty frontier emerging markets to shine.

Source: Bloomberg.

Note: Indexes used are MSCI EM Equal Country Weighted and MSCI Emerging Markets.

5. Cheaper and growthier

If an asset’s price is declining, we believe it could be a good investment in the case that the underlying fundamentals are solid and the valuation is becoming cheaper only because the market is selling for non-fundamental reasons. Conversely, we tend to dislike investments which are increasing in price due to valuation gains while the underlying fundamentals are deteriorating.

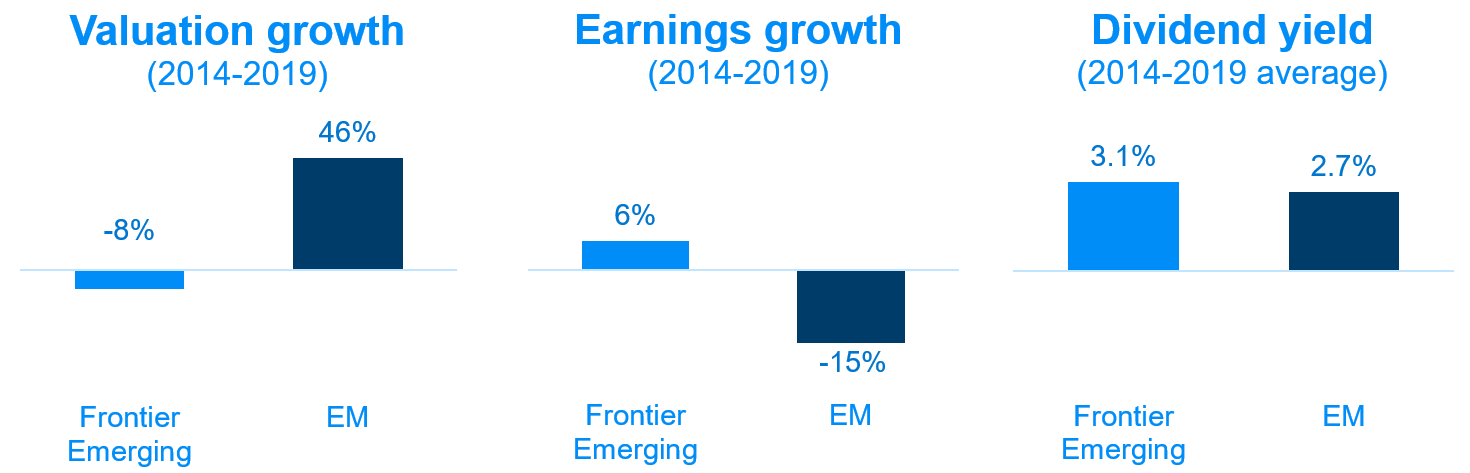

Frontier emerging markets have not only gotten cheaper over the past seven years since we launched our fund, but their underlying earnings are growing. Meanwhile, the mainstream EM index has gotten more expensive while earnings have contracted. On top of that, frontier emerging markets have, on average, produced a greater dividend yield. Additionally, they tend to be higher quality given their higher returns on equity and lower debt load. These fundamental and pricing differences make frontier emerging markets a compelling choice over the mainstream index.

Source: Bloomberg.

Notes: Indexes used are MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI Frontier Emerging Markets. 2020 was excluded due to the short-term impact of COVID-19 on earnings.

Conclusion

Actively investing outside the mainstream EM index adds both diversification and performance benefits to a prudent investor’s portfolio. The 50 frontier emerging markets attract far fewer investors and are less efficient than the large (and debatably developed) emerging markets such as China, Taiwan, and Korea which dominate the mainstream EM index. This offers a benchmark-agnostic active investor a great number of opportunities to find overlooked cheap, growing, high-quality companies. In the past several years, valuations in these smaller emerging markets have become cheaper, while earnings have grown faster and quality tends to be higher than in the large EM, making them a land of abundance for hidden-gem seekers.

After a long cycle of frontier emerging markets underperforming relative to China, the time has come for the “forgotten fifty” to lead again.

Learn more about our Evli Emerging Frontier Fund

Our recent blogs

The case for emerging markets: It’s about time

Testing our portfolio for COVID-19: Why we sold Turkey

The value of investor meetings: Five things we learned from interviewing 323 CEOs last year

+1,000% during COVID-19: Protecting our portfolio with Malaysian medical gloves

A month in Turkey: Retreating from coronavirus

A month in South Africa: The road to nowhere

A month in Saudi Arabia: Piercing the veil

A month in Vietnam: Closing the deal

A month in Thailand: Driving three hours to see an empty factory

A month in Pakistan: An altercation at the ministry of finance

A month in Bangladesh: We're investing billions in the world’s best stock market

A month in Indonesia: Offending Trump in Bali

A month in Malaysia: Finding another gem on "Treasure Island"

A month in the Philippines: How active management helped us beat the traffic (and the market)