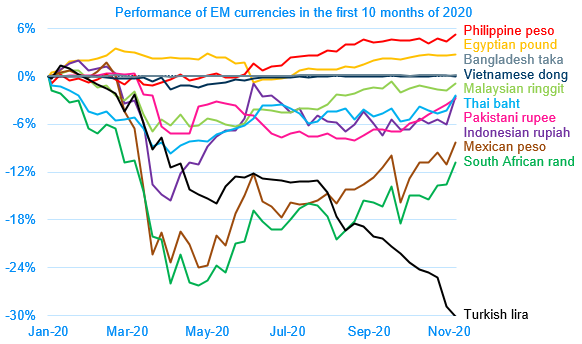

Investing in Turkey is a roller-coaster ride. Just two years ago, we experienced first-hand the brunt of a local currency crisis that cost our fund 11%. Now, as the pandemic continues to hammer across the globe, no other emerging market has been cracking under pressure noticeably more than Turkey. This led us to sell all four of our compelling Turkish investments in August.

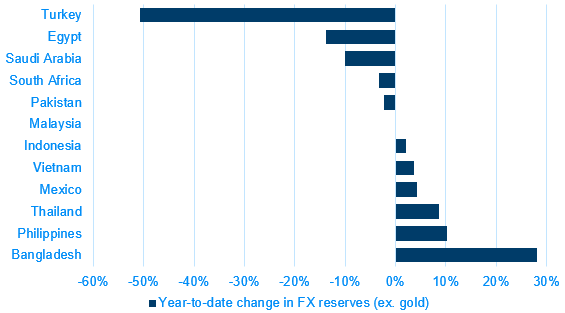

To better understand what drove our decision, we need to go back earlier this year when the Turkish central bank and state-run banks had been aggressively selling dollars to prop up the lira and boost economic growth. In just the first four months of 2020, Turkey had already sold more dollars than it did in all of 2019, burning through its reserves faster than any other emerging market we invest in.

Despite the banks’ efforts, the lira was set to slide. Questionable independence of the central bank, persistently high inflation, large share of imports as well as weak exports in the country’s trade balance, a pandemic drop in tourism revenues, alarmingly dwindling reserves, and external financing gap have been brewing up the perfect recipe for a balance-of-payments crisis. Fitch changed Turkey’s rating outlook to “negative” while Moody’s downgraded Turkey’s rating to ‘B2’, or ‘junk’, citing “increasing external vulnerabilities, eroding fiscal buffers and unwilling institutions” as major culprits. Both moves were met with disdain by President Erdogan who retorted that Turkey is under “economic attack” and that “ratings don’t count for anything.”

We believed the lira was highly likely to continue succumbing to these downward pressures. As stewards of our fund's capital, we choose to safeguard our clients' assets and avoid unnecessary currency risks, and so we decided to exit all of our Turkish positions (which we bought only a few months earlier) in August. All of those were very strong companies with impressive growth, cheap valuations, and resilient balance sheets. However, as we learned back in 2018, in a currency crisis like this the whole market loses value in hard currency: almost no company is spared, regardless whether it is an exporter that’s supposed to come with a natural hedge or a counter-cyclical business that’s supposed to prosper in bad times.

The decision paid off: since then, the lira has depreciated by another 10%, reaching a new anti-record of over 8 liras per dollar, and the shares we sold performed worse than the rest of our portfolio in EUR terms.

The lira weakening against the U.S. dollar by more than 20% over the last year extends Turkey’s undesired record of currency depreciations of at least 20%, marking the currency's 13th such instance over the past 30 years – the highest frequency among 18 emerging markets. We will continue monitoring the currency and macro risks before returning to this market.

Assessing market vulnerability

Our decision to sell Turkish holdings came as a result of our broader effort to evaluate the potential impact of COVID-19 on the emerging markets we have exposure to. Since the pandemic erupted, in order to assess the level of vulnerability of our markets, we used six metrics: 1) GDP growth forecasts, 2) reliance on oil and tourism, 3) monetary policy space, 4) fiscal policy space, 5) reserve adequacy, and 6) financial strength. We go through our analysis below.

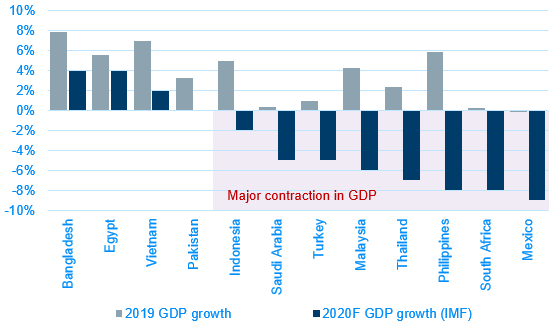

1. GDP growth (or lack thereof)

When the pandemic forced the world to stay shut, a lot of economic activity dissipated overnight. The unique combination of stringent lockdowns, weak consumer demand, and investment cutbacks have caused output and consumption to drop significantly. As a result, the global economy is projected to contract by nearly 5% this year, much worse than in the financial crisis of 2008-09. Emerging markets should fare better but are also vulnerable given their less diversified economies and fragile healthcare systems. The IMF projected the group to contract by 3% this year, with as many as 100 million people pushed into extreme poverty.

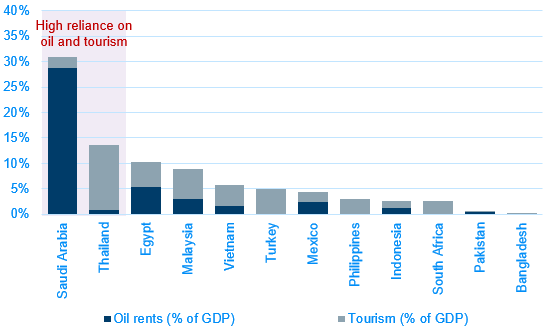

2. Reliance on oil and tourism: diversification is key

However, not all emerging markets are impacted similarly. Some countries are particularly hit given their greater exposure to certain economic sectors that are expected to bear the brunt of the pandemic. For example, Thailand’s tourism revenues (13% of GDP) have plunged as borders were closed and non-essential travel got suspended, while the plummet in energy prices has jolted Saudi Arabia’s oil revenues (29% of GDP), leading its reserves to fall at the fastest pace in at least two decades. On the other hand, countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam are still forecast to grow 2this year at the rates of 4% and 2% respectively.

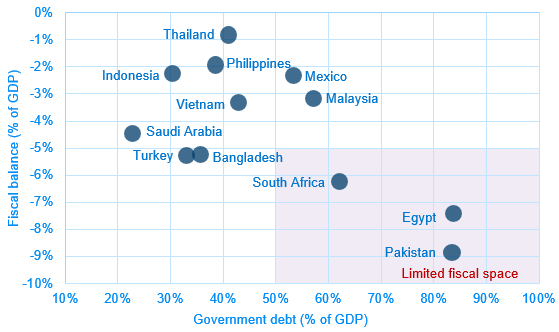

3 and 4. Monetary and fiscal policy: not enough space

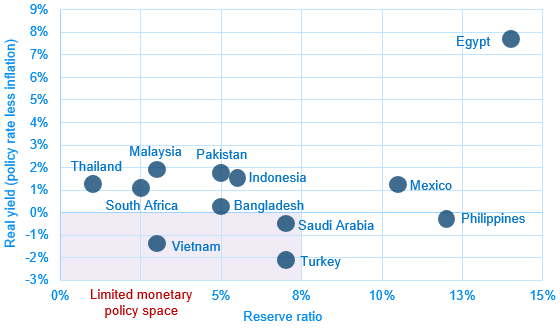

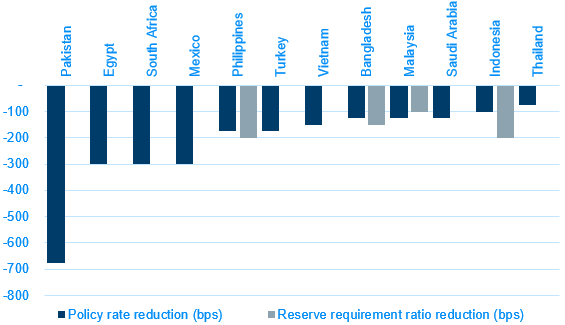

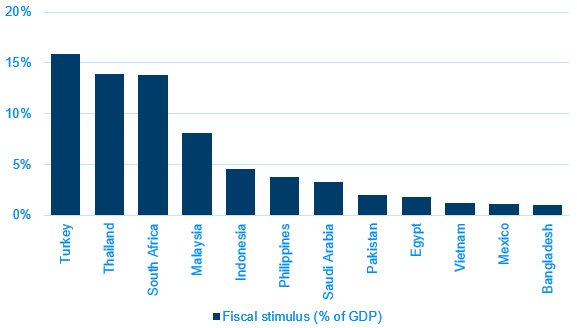

Before the pandemic began, conventional policy actions were already reaching their limits in some countries. For instance, Pakistan and Egypt had over 7% fiscal deficits (as a % of GDP) while also carrying high government debt levels as compared to their peers, thus hindering their ability to spend and borrow more without investors having to sound the alarm on their fiscal sustainability, while Turkey and Vietnam whose real yields (policy rate less inflation) were -2.1% and -1.4% respectively had limited capacity to further ease monetary policy.

During the pandemic, emerging markets' governments attempted to stimulate their economies to the extent made possible by their pre-existing conditions. While a country like Turkey with limited monetary policy space has rolled out a series of fiscal packages equivalent to 16% of its GDP, countries with the weakest fiscal space had to implement the deepest monetary policy rate cuts and turn for the international support once again: Pakistan, South Africa and Egypt have availed a combined $13.7b in emergency financing from the IMF. Vietnam is a special case: while not being able to unleash massive fiscal or monetary stimuli like some of its emerging peers, a very effective approach to managing the pandemic on the ground helped the country avoid a healthcare crisis, allowing it to get back to normal rather swiftly.

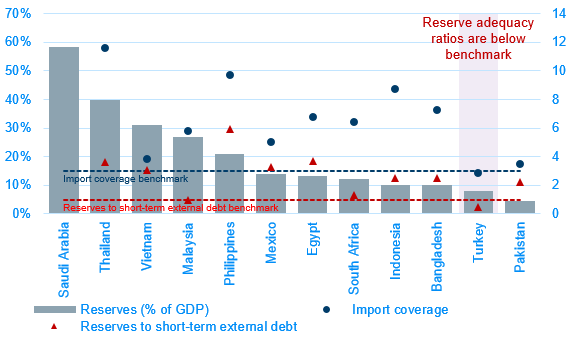

5. Reserve (in)adequacy

To weather a crisis, an economy – particularly a developing one – should have sufficient hard-currency reserves as a form of protection. As a rule of thumb, reserves must cover at least 3 months’ worth of imports (import coverage) and 100% of short-term external debt. If a country’s reserves are inadequate, it will be challenging for it to cope with a sudden capital flight resulting in a market panic and an economic shock. With capital fleeing emerging markets, the lethal combination of diminishing exports and tourism activity could cause reserves to dry up. This scenario rings loudly for Turkey. Before the pandemic started, its reserves had already fallen to dangerously low levels making them insufficient to cover the country’s short-term external debt and three months’ worth of imports.

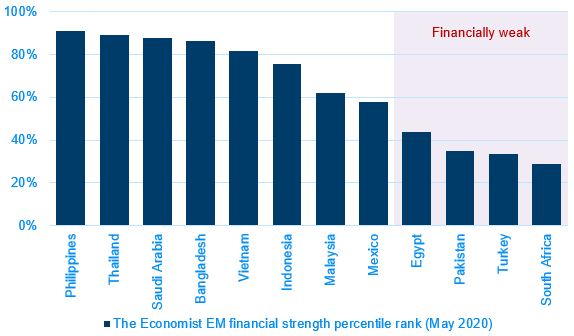

6. A matter of financial strength

Earlier this year, The Economist published a ranking of 66 emerging markets based on four measures of financial strength: cost of borrowing, reserve cover, and public and foreign debt (% of GDP). It aimed to show which emerging markets are relatively stable and which are in distress. Based on this assessment, most of the markets we invest in rank favorably relative to their peers. As for the financially weaker ones, these include the usual suspects: Egypt, Pakistan, Turkey, and South Africa.

Testing our markets for COVID-19

Emerging markets have always been known for their growth: despite higher risks, investors have been looking at these markets to capture higher returns. However, when the pandemic kicked into high gear, most of that growth disappeared, and instead the long-standing vulnerabilities were exposed. Our framework to assess these vulnerabilities through six different metrics discussed earlier is presented below. While it is not intended to be exhaustive, it aims to shed light on the resilience of our markets during the pandemic.

.png)

The results paint a varied picture of the COVID-19 impact on emerging markets, with no one country excelling in all parameters but with some performing better than others overall. Based on our analysis, we sold our entire Turkey position and reduced our exposure to Thailand and South Africa.

Looking beyond the pandemic

As COVID-19 continues its painful march across the globe, we will continue monitoring its impact on the markets we invest in to avoid outsized macro risks. Most importantly, we will continue looking for cheap high-quality companies that are growing in both good and bad times, in and out of the pandemic. So far, we have managed well: since the beginning of the year, our fund is up 8% in EUR, and is in the top 5% among peer funds investing in frontier and small emerging markets, beating the average emerging market index by over 25%.

.png)

Learn more about our Evli Emerging Frontier Fund

Our recent blogs

A month in Turkey: Retreating from coronavirus

A month in South Africa: The road to nowhere

A month in Saudi Arabia: Piercing the veil

A month in Vietnam: Closing the deal

A month in Thailand: Driving three hours to see an empty factory

A month in Pakistan: An altercation at the ministry of finance

A month in Bangladesh: We're investing billions in the world’s best stock market

A month in Indonesia: Offending Trump in Bali

A month in Malaysia: Finding another gem on "Treasure Island"

A month in the Philippines: How active management helped us beat the traffic (and the market)