The Fed chair Jerome Powell declared it’s time to cut rates at Jackson Hole.

The inflation scare has largely abated, only to be dethroned by economic growth scares as the source of market consternation. Are growth fears legitimate and are we headed towards recession?

“It’s time”

At the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole summit, Fed chair Jerome Powell declared it’s time to cut rates. The anticipated announcement marked the end of a tumultuous era in monetary policy. The tumultuousness was a product of the corona shock. Before the pandemic, we lived in a macroeconomic Eden of called the great moderation. The moderation meant low macro volatility with stable economic growth and low and stable inflation. In turn low inflation enabled low interest rates. Even Eden there are snakes, and low interest rates inflamed a bubble in technology stocks and a few housing bubbles. The corona shock cast the modern man from this paradise and ushered a brief but highly inflationary era.

The “it’s time” comment meant that inflation has subsided sufficiently and risks to economic growth have risen enough for central banks to cut rates. Markets expect the Fed to cut rates by one percentage point by the end of the year and the ECB to follow its first cut by another two cuts. Then central banks will proceed chopping away. What remains undetermined is the pace of cutting.

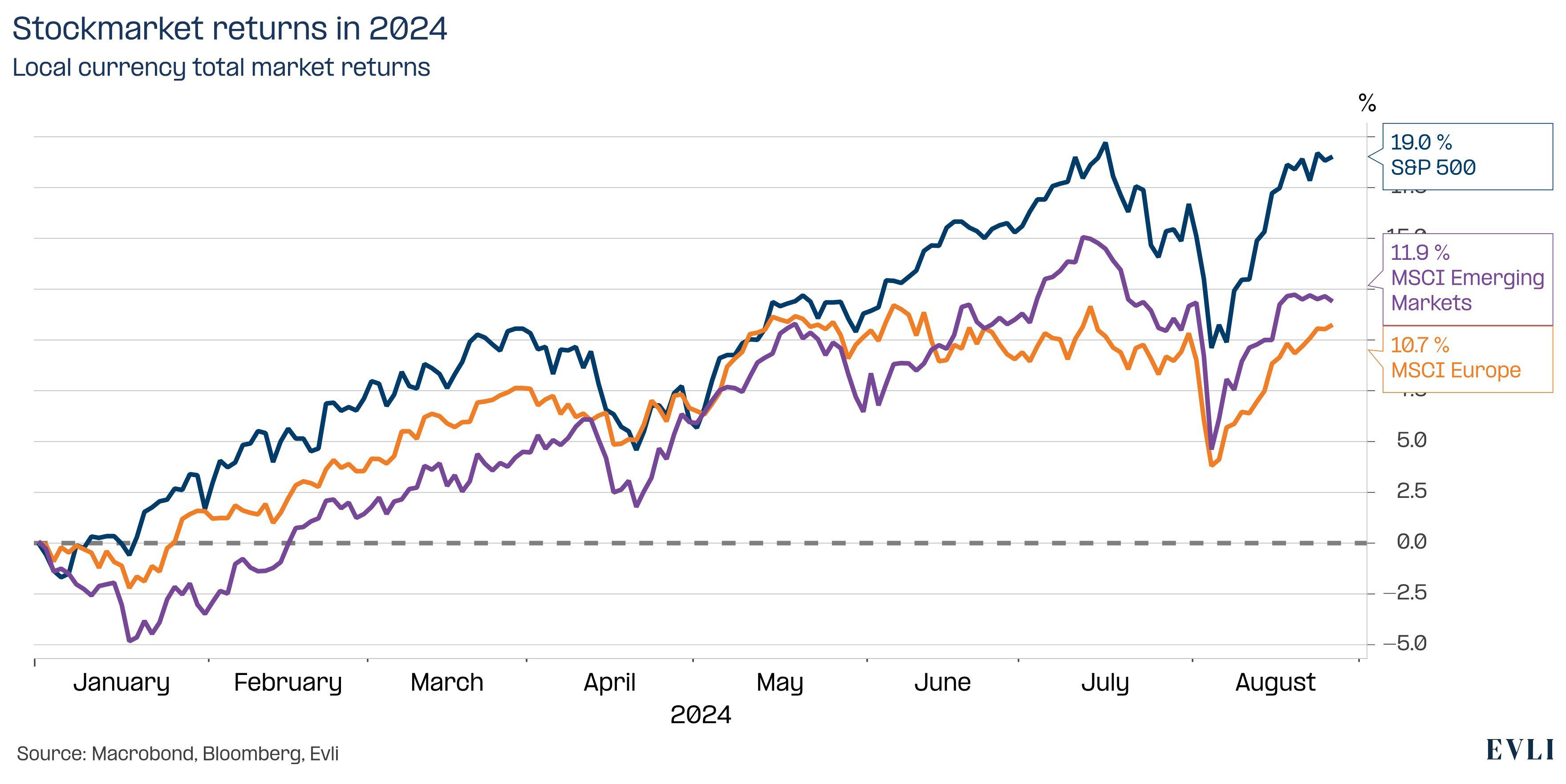

Figure 1: A strong year in progress on the stock market

Growth scare

Economic growth jitters have displaced fears of unrelenting core inflation. The nexus of fear is the US jobs market. The US jobs market is clearly slowing as one can see both in terms of the unemployment rate and the jobs rate.

Since April 2023 US unemployment rate has risen from a five-decade low of 3.4 by almost a percentage point. The rise in the unemployment rate triggered the Sahm rule, where a sharp rise in unemployment is historically indicative of recession.

The Sahm rule is intuitive. In a recession firms experience falling sales. Firms respond to falling sales by cutting costs, which means laying off employees. Hence a rapid rise in unemployment should signal falling demand and hence recession. The Sahm rule has only once, in the mid-1960s, not meant recession in the US.

The Sahm rule does not work well except in the US

Sahm herself is on record saying that she thinks her rule has misfired. And it probably has. Firstly, whilst her rule has worked well in the US, it has not worked elsewhere. A rule that works in only one country is more of an exception than a rule.

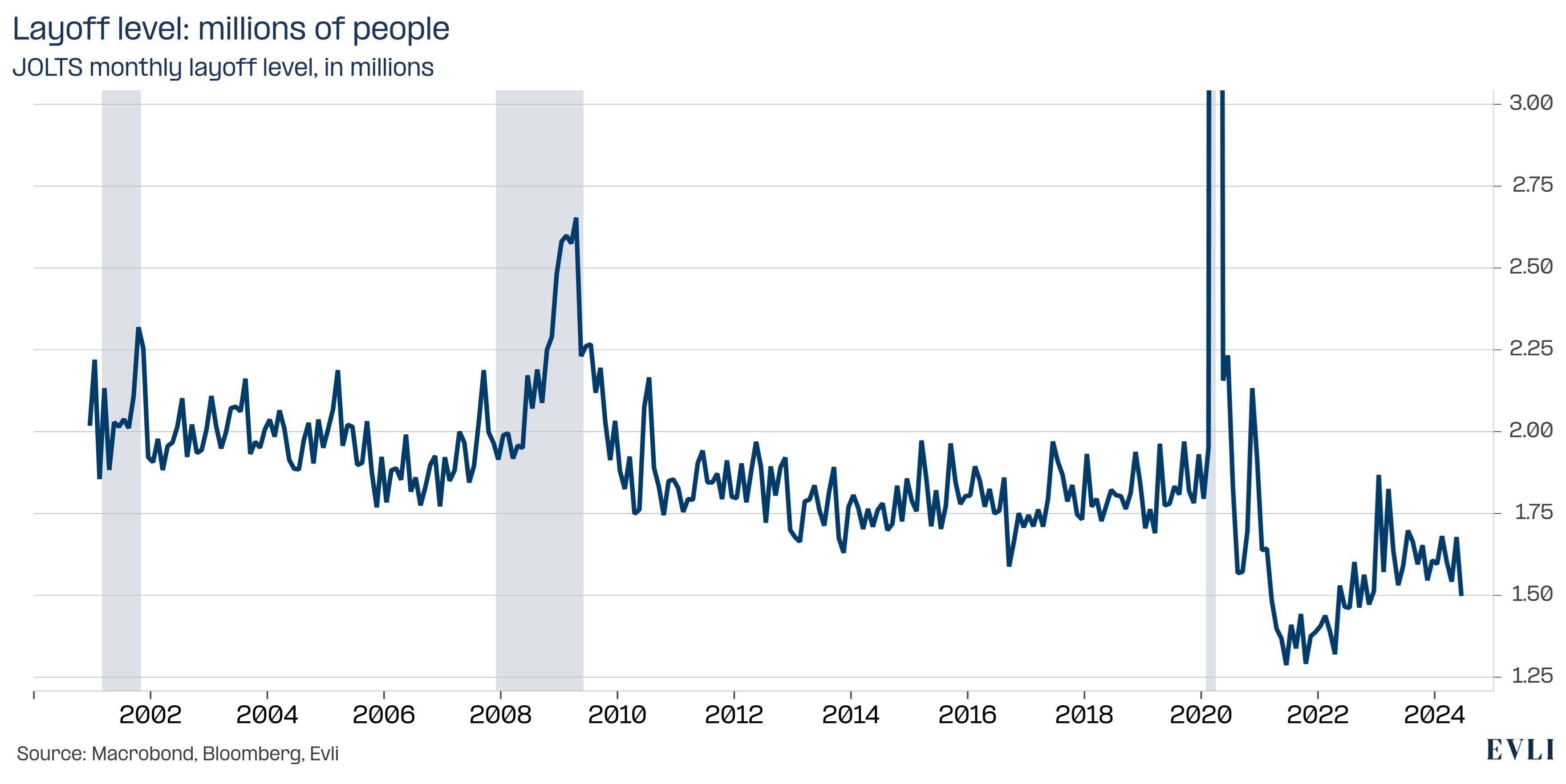

But the reason Sahm’s rule is misdiagnosing the US economy, is the fact that US layoffs are at a historical low. Only 1.5 million US workers were permanently laid off in June, which is lower than during any year since 2000. It’s difficult to think of the economy being under strain if layoffs are at a historical low.

Figure 2: Layoffs in the United States are at a historically low level

Go West, young man

Unemployment is rising because of rapid immigration. Immigration in 2022 and 2023 amounted to a total of over seven million people, whilst between 2014 and 2021 immigration averaged less than one million per year. Immigrants tend to be younger than the native labour force and hence the US labour markets has faced a wave of new workers, which it has been unable to absorb. The immigration wave has been significant both in terms of increasing labour supply and driving economic growth. Immigration on such a scale is rare, and such historical exceptions are precisely the reason why one has to be careful with historical rules of thumb.

The US economy growing at a rate of over two percent

Looking at growth itself, the US economy expanded at an annualised rate of 3 percent in Q2. The Fed’s most recent estimate of long run GDP growth is 1.8 percent. Most economists expect growth to slow towards trend growth.

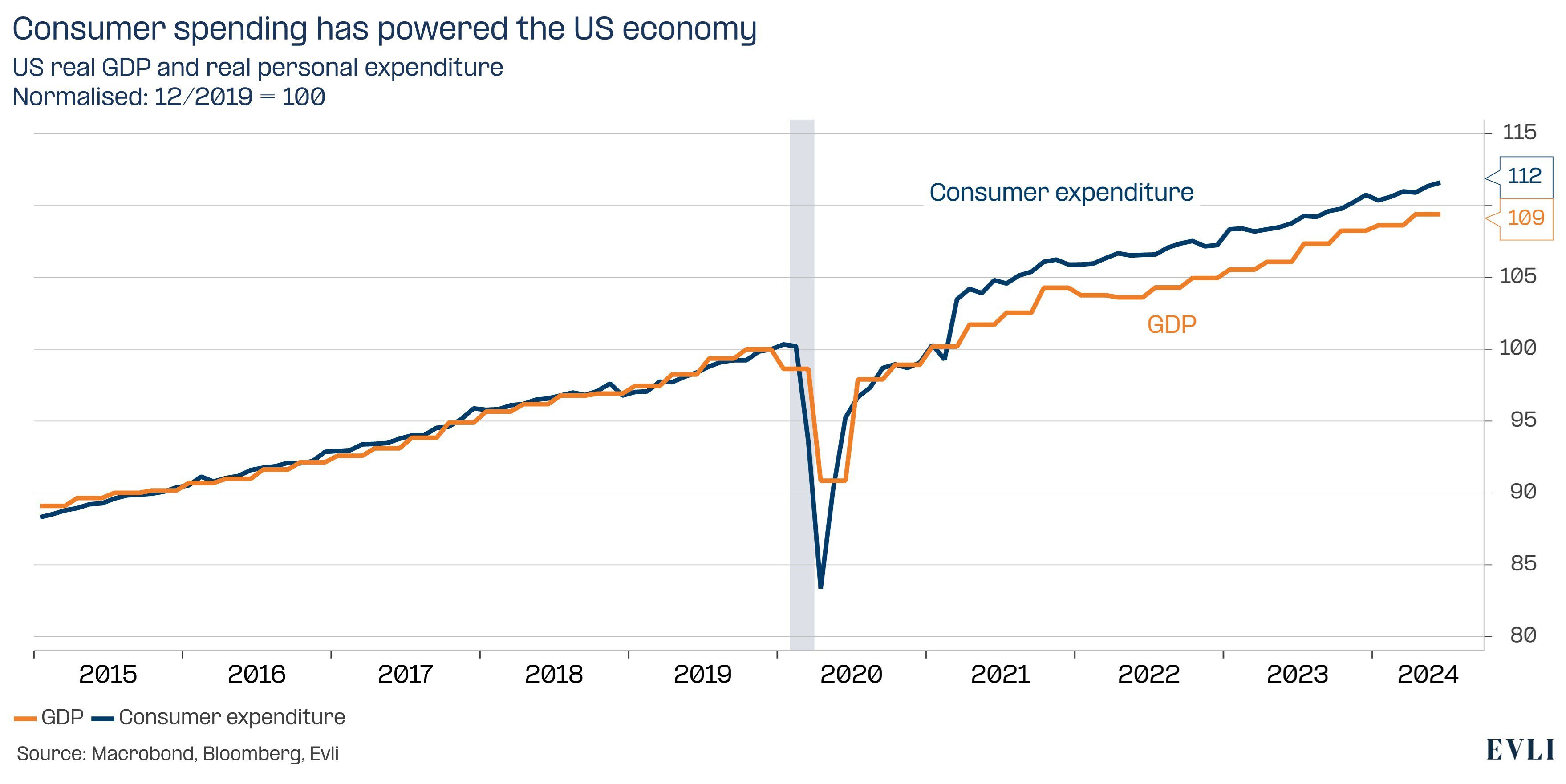

The engine of US growth has been private consumption and investment, with government spending adding a further strength.

As immigration recedes a noticeable tailwind will end. US household saving has fallen to a very low 2.9 percent, so deceleration seems inevitable.

Hence it makes sense that growth will slow towards trend growth and the labour market will cool off. The Fed’s rate of monetary easing will be important in guiding the economy to trend growth.

Figure 3: The consumer is the engine of economic growth in the United States

The Trump card

A further twist will be dealt in the US elections in November. In terms of economic growth neither Donald Trump nor Kamala Harris seems overtly obsessed with the US deficit and hence government should continue to support the economy. Republican fiscal hawks have all but gone extinct. Hence the impact of elections is more relevant from a burden sharing perspective. Will spending be funded by corporations or individuals, taxes or tariffs.

Expansions don’t die of old age

When looking at evidence of the economic expansion slowing down, it’s useful to remember that economic expansions don’t die of old age, but due to an exogenous shock. The last three economic expansions lasted close to seven, ten and eleven years. None of these ended due to natural causes. The immediate cause respectively was a dot-com bubble, a financial crisis and a pandemic shock.

Of course, apart from the corona crisis none of these few shocks was truly exogenous. Easy monetary policy contributed to the housing boom that led to the financial crisis. Hence policy error is another serial killer of economic expansions. And that is a powerful reason for Powell to cut rates.